Landmark $300bn for poor countries in climate agreement

Eko Siswono Toyudho/Getty Images

Eko Siswono Toyudho/Getty ImagesRich countries have pledged a record $300bn (£238bn) to help developing countries fight climate change, but the deal faces criticism that it does not come close to solving the challenges facing poor countries from global warming.

Negotiations at the UN climate conference COP29 in Azerbaijan ran 33 hours late, and fell by just a few centimeters.

The head of the UN’s climate agency, Simon Stiell, said “it has been a difficult journey, but we have brought an agreement.”

But the negotiations also failed to progress to the agreement that was passed last year for the countries to “separate from burning”.

Developing countries, and countries most at risk of climate change, were surprisingly absent from the talks on Saturday afternoon.

“I am not exaggerating when I say that our islands are sinking! How can you expect us to return to the women, men, and children of our countries with a bad deal?” said the chairman of the Alliance of Small Island States, Cedric Schuster.

But at 03:00 local time on Sunday (23:00 GMT on Saturday), and after some changes to the agreement, the countries finally passed the agreement. There was cheering and applause, but the angry speech from India showed that great frustration remained.

“We cannot accept it… the proposed objective will not solve anything. [It is] it is not compatible with the climate action needed for our country to survive,” said Leela Nandan at the conference, calling this amount too small.

Then countries including Switzerland, the Maldives, Canada and Australia protested that the language about reducing the global use of fossil fuels was too weak.

Instead, that decision has been postponed until the next climate talks in 2025.

This promise of more money is a recognition that poor countries are bearing the brunt of climate change, but also have historically contributed little to the climate crisis.

The newly pledged money is expected to come from government subsidies and private sector – banks and businesses – and should help countries transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

There was also a commitment to triple funding to prepare countries to deal with climate change. Historically, only 40% of available climate change funding has reached this goal.

As well as the $300bn (£238bn) pledge, countries have agreed that $1.3tn is needed by 2035 to help tackle climate change.

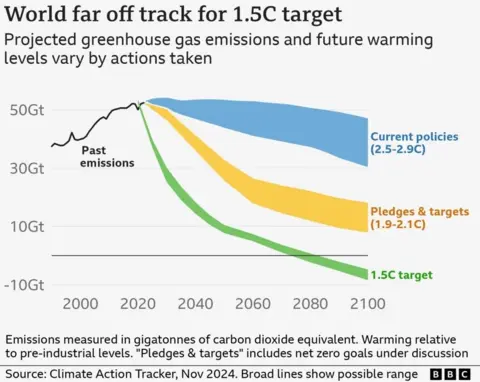

This year – we are now “certainly” going to be the warmest on record – hit by intense heat waves and deadly storms.

The opening of these talks on November 11 was inspired by the election of US President Donald Trump, who will take office in January.

He is a climate skeptic who has said he will pull the United States out of the historic Paris Agreement in 2015 to create a roadmap for countries to deal with climate change.

“It definitely brought down the title number. Some donors from developed countries know very well that Trump will not pay a penny and they will have to return this money,” said Prof. Joanna Depledge, an expert on climate negotiations at Cambridge University, told the BBC.

Reaching this agreement is a sign that countries are still willing to work together on climate, but with the world’s largest economy now not participating, it will be difficult to meet the multi-billion dollar target.

“The protracted end game at COP29 shows the difficult global situation we find ourselves in. The result is a flawed consensus between donor countries and the most vulnerable countries in the world,” said Li Shuo of Asia Society Policy. Institution.

UK Energy Secretary Ed Miliband stressed that the new pledge does not obligate the UK to come up with additional climate finance but is in fact “a huge opportunity for British businesses” to invest in other markets.

“This is a critical eleventh hour climate agreement. It’s not everything we or others wanted, but it’s a step forward for all of us,” he said.

In order to receive the promised additional income, developed countries including the UK and the European Union are demanding a strong commitment from countries to reduce the use of fossil fuels.

Despite their hopes that the agreement reached at talks in Dubai last year to “move away from fossil fuels” would be strengthened, the final proposed agreement has been repeated.

In many countries this was not good enough, and was rejected – now it will have to be agreed next year.

Countries that depend on oil and gas exports are reportedly fighting an uphill battle in negotiations to stop further progress.

“The Arab group will not accept any text targeting certain sectors, including fossil fuels,” Saudi Arabia’s Albara Tawfiq said at an open meeting earlier this week.

Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Sean Gallup/Getty ImagesSeveral countries came to the talks with new plans to deal with climate change in their countries.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has made a play for global climate leadership and pledged to cut UK emissions by 81% by 2035, which was celebrated by many as an aspirational goal.

The host country, Azerbaijan, was a controversial choice for the climate talks. It says it wants to increase gas production by a third over the next decade.

Brazil is seen as the best way to host next year’s climate conference, COP30, in the city of Belém due to President Lula’s strong commitment to climate change and to reducing deforestation in the globally important Amazon rainforest.

Source link